“A Shared Inquiry into Shared Inquiry” in the public history classroom

25 October 2017 – Jeff Manuel

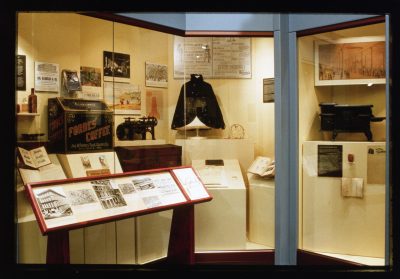

Display from “St. Louis in the Gilded Age” exhibit, Missouri History Museum, curated by Katherine T. Corbett, St. Louis, Missouri, 1994. Photo credit: Missouri Historical Society, St. Louis.

When Tammy Gaskell posted to the History@Work blog asking public history educators to recommend articles from The Public Historian that work well in the classroom, I immediately replied with several options. At the top of my list was Katherine Corbett and Dick Miller’s “A Shared Inquiry into Shared Inquiry,” which appeared in the winter 2006 issue. I teach an introductory public history course at a regional public university in Illinois. Students in my class are usually a mix of undergraduate history majors, MA students, and those for whom the class fit their schedule. I typically assign Corbett and Miller’s article early in the semester, and it works well for several reasons. First, it offers students a clear introduction to the concepts of shared inquiry and shared authority, which are central to public history. Second, it raises many of the theoretical issues that students need to wrestle with in an introductory public history course, including collaboration, the divide between history and heritage, and the role of funding in shaping historical interpretation. Finally, the article is beautifully written. Students appreciate this in any reading assignment, but it’s especially welcome when I am trying to emphasize the need to write clearly for nonacademic audiences.

Corbett and Miller’s article gets students to wrestle with the concepts of shared inquiry and shared authority, which, in my opinion, are signature pedagogies of public history.[1] The discussion of shared inquiry is often the moment when students realize that a course in public history is more than vocational training to work in a museum or a class about monuments. It forces them to wrestle with public history as a complex, theoretically minded approach to history rather than a body of material to master. It is often when students realize the class will challenge them in a very different manner than other history courses. Corbett and Miller put it best: “honest sharing, a willingness to surrender some intellectual control, is the hardest part of public history practice because it is the aspect most alien to academic temperament and training” (36). Once the concept is introduced via Corbett and Miller’s article, it serves as a touchstone for later discussions and projects. Corbett and Miller raise questions that I continue to ask students throughout the class: Who has power in this situation? Is it possible to do good work as a historian in this project? Once they are asking themselves these questions, they are beginning to think like public historians.

In my experience, students eagerly embrace the concepts of shared inquiry and shared authority once they understand them. At times they embrace them a little too eagerly. A vague and romanticized “community” can become all-knowing and all-powerful. Or discussions can become attacks on “academic history” that lack nuance and sophistication (but occasionally hit the mark). To push back, I now assign Michael Frisch’s thoughtful reflection on shared authority and Andrew Hurley’s excellent description of community-engaged scholarship in St. Louis.[2] We then have the foundation for a rich discussion of shared inquiry and the trade-offs inherent in community participation and marshaling academic expertise.

Missouri History Museum. Photo credit: Missouri History Museum is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Corbett and Miller’s article is an excellent introduction to the idea that, “public history is always situational and frequently messy” (19). Public history is practice-based and therefore quite different from other history courses most undergraduates encounter (especially those not in a public history program). There are theories and approaches to learn, but they always play out through case studies that are situational and can’t be generalized. One reason Corbett and Miller’s article works so well for me is that many of their examples are drawn from the Missouri History Museum, which many students at my university know and have visited. For my midwestern students, examples of cutting-edge practices at the Tenement Museum or highbrow European sites are interesting but can feel distant, both geographically and culturally. Public history education is also situational. What makes a good reading depends on the students you teach and where you are located.

When introduced early in the semester, Corbett and Miller’s article is a good launching pad for discussing why collaboration is central to public history. Selfishly, the article gives me justification for assigning group projects. Student aversion to “group work” is common, but Corbett and Miller’s reflections on shared inquiry highlight how any good public history work is shared, that is, collaborative. They give helpful examples of the many hands involved in putting up an exhibit. Discussion of the article has also been a good time to take an inventory of my students’ skills with an eye toward how they might contribute to team projects. I usually ask students to talk about skills they have developed in other courses or outside of school. I’m always pleasantly surprised by students’ multifaceted skill sets, which include exhibit fabrication, multimedia editing, and even quilting or scrapbooking. It takes some prodding, but once students realize their hobbies and passions could be valuable to public history coursework they often engage in the class with a newfound vigor.

As I planned my public history class for this year, I reflected once again on Corbett and Miller’s article and the questions it raises. I knew I’d assign it to my students early in the semester. But with controversy over a Confederate memorial raging in St. Louis and the national debate over so-called fake news, I wonder whether I should assign more readings that emphasize historians’ authority in such debates. More broadly, while syllabus planning I am always uneasy teaching about shared authority without actually sharing authority with the students in my classroom. “Sharing authority is a deliberate decision to give up some control over the product of historical inquiry,” Corbett and Miller write. It is easy to critique this when reading about public history projects somewhere else, but I find it much harder to implement when I’m designing my classes. I have experimented with student-created lessons and even leaving weeks of the syllabus blank for student-led topics. So the debate continues. Nonetheless, guided in part by Corbett and Miller’s article, I look forward to the conversation.

~ Jeff Manuel is associate professor of history at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, where he teaches classes in public, oral, and modern US history.

[1] By “signature pedagogy,” I refer to the literature on the distinctive pedagogies within a discipline that properly prepare students to think and work as professionals in that field. Lee S. Shulman, “Signature Pedagogies in the Professions,” Daedalus 134, no. 3 (Summer 2005): 52–59. The application of signature pedagogies to history is described in Lendol Calder, “Uncoverage: Toward a Signature Pedagogy for the History Survey,” Journal of American History 92, no. 4 (March 2006): 1358–70. Note that Patricia Mooney-Melvin argues that the broader category of “reflective practice” is the true signature pedagogy of public history.

[2] Michael Frisch, “From A Shared Authority to the Digital Kitchen, and Back,” in Letting Go? Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World, ed. Bill Adair, Benjamin Filene, and Laura Koloski (Philadelphia: Pew Center for Arts and Heritage, 2011), 126–37; Andrew Hurley, Beyond Preservation: Using Public History to Revitalize Inner Cities (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010).

Editor’s note: The post is the third in a series commissioned by The Public Historian that focuses on essays published in TPH that have been used effectively in the classroom. We welcome comments and further suggestions! If you have a TPH article that is a favorite in your classroom, please let us know. You can send your suggestions to [email protected].