Graduate student project award: The Lost Museum

07 April 2015 – Jenks Society

Editor’s Note: This series showcases the winners of the National Council on Public History’s awards for the best new work in the field. Today’s post is by the students of the Jenks Society for Lost Museums, creator of a unique exhibition in the Brown Public Humanities Program.

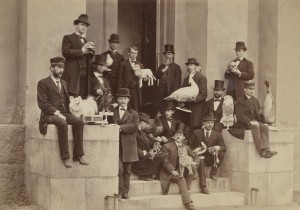

J.W.P. Jenks with his taxidermy students, 1875. Photo credit: John Hay Library and Brown University Archives

It circulated as a bit of campus lore: the curious tale of the Jenks Museum of Natural History, which once existed at Brown University.

As graduate students in Brown’s Public Humanities program, we were intrigued when we first heard about the long-gone Jenks Museum. We spend much of our time thinking about preservation and memory, so the idea of a lost museum at our university resonated with us. We began to imagine recreating the museum as a class project on the occasion of Brown’s 250th anniversary. In the fall of 2013, a group of ten students with a range of backgrounds in the arts and humanities joined forces to carry out this work. We called ourselves the Jenks Society for Lost Museums.

As we delved into the archives, the story of an eccentric New England naturalist and the museum he created revealed itself to be poignant and conceptually rich. The fate of the Jenks Museum reflects the transition from natural history to experimental biology in the university context. It demonstrates the ephemerality of museum collections and the relentless decay that consumes all things. It is also a tale of how one man’s life-work fared against the momentum of a changing world.

Naturalist John Whipple Potter Jenks founded the museum in 1871. For Jenks, a pious collector who sought to represent the glories of divine creation, the museum represented a nigh-religious calling. He curated the collection of more than 50,000 objects for decades, despite the university administration’s increasing apathy. In 1894, weakened by the arsenic used in his taxidermy preparations, Jenks collapsed and died at his post. A former student referred to him as a “martyr to science.”

Soon after Jenks’ death, the rising generation of biologists dismantled the museum and packed the collection away. They did not share Jenks’ zeal for natural history, viewing the stuffed birds, horse skeletons, curiosities, and assorted ethnographic objects as old-fashioned. Jenks’ collection mouldered in storage until about 1945. At that point, needing space for new laboratories, the biologists hauled the bulk of the collection–ninety-two truckloads of specimens–to a university dump by the Seekonk River.

In terms of curating an exhibition about the Jenks Museum, the Jenks Society faced a challenge: the scarcity of material from its collection. But this absence also represented the crux of the story and an important aspect to accentuate. Without celebrating nineteenth-century natural history practices, we wanted to explore how objects that so much effort went into making and collecting could be thrown away as worthless. By taking an experimental approach to public history–combining contemporary art and historical methods–we could re-imagine the museum as a meditation on life, death, and decay within a larger narrative of the history of science.

We invited artist Mark Dion to join the project as an advisor. In his work, Mark uses techniques of museum display to critique museums and their representations of nature. (See, for example, his installation at the Musée Océanographique in Monaco.) Our professor, Steven Lubar–an expert in the realm of museum history–guided us through the process and offered curatorial counsel.

Ultimately, we re-collected the Jenks Museum using three different museological media: a period room (“what was”), a case of historical artifacts (“what happened”), and a display of contemporary art (“what might have been”). We installed these in Rhode Island Hall, the campus building that once housed the Jenks Museum.

The period room represents J.W.P. Jenks’ workshop on the day of his death. Conceived as a kind of theatrical set-piece, the assemblage of objects subtly symbolizes incidents from Jenks’ life and his mindset. A giant Bible towers over his desk, while a book by Darwin sits under a chamber pot, for example. We acquired most of these props inexpensively at flea markets.

A small number of objects from the original Jenks Museum have survived in area repositories, many of them in poor condition. We borrowed about one hundred of these and arranged them in a display case in order of their decay, showcasing broken things and disintegrating fragments. A large, well-preserved mastodon tooth gives way to crushed eggs, a battered taxidermy mouse, and labels handwritten by Jenks for things that no longer exist.

We issued an open call to artists, inviting them to recreate lost objects from the Jenks Museum, all in white. We offered each participant a choice of three different Jenks objects to remake, frozen in time with their archaic nineteenth-century descriptions: “Ancient arms and armor / A superior specimen of the rare sponge Euplectella / A fine skin of a walrus,” for example. Students at the nearby Rhode Island School of Design and local Providence artists contributed a number of these works, but we also received submissions from as far afield as the United Kingdom. We labeled these objects with Jenks Society accession numbers and placed them in a room marked “Museum Storage.”

When our “Lost Museum” exhibition opened, we anticipated a primary audience of members of the Brown and RISD communities. But thanks to local, national, and international media coverage–including a feature in the New York Times–the exhibition has attracted thousands of visits, drawing a much wider audience than expected.

We attribute the success of the exhibition in part to its mysteriousness and openness to visitor interpretations. The hybrid methods of art and history enabled us to balance historical accuracy, emotional truthfulness, and a degree of abstraction. We left certain aspects of the display unexplained and left some points unstated, inviting visitors to put together the pieces and make their own meaning. Comedy, tragedy, and weirdness co-exist in The Lost Museum.

To learn more about the Jenks Society, please visit our web site, stop by our pop-up exhibit at the NCPH conference in Nashville, or attend our upcoming event in Providence: “Lost Museums: A Symposium on the Ephemerality & Afterlives of Museums & Collections.”