"Don’t frack our history!" Using the past for environmental activism in northeastern Pennsylvania

28 September 2012 – Jeff Robinson

“I am from a small agrarian town in northeastern Pennsylvania – just south of Binghamton, New York and north of Scranton, Pennsylvania,” is what I told people in Boston when I first moved to New England to start graduate school in 2008. After all, with the exception of a few folks I serendipitously encountered from the area, Montrose, Pennsylvania remained a little dot on the map; a place completely off the periphery of the Massachusetts intelligentsia…or so I thought.

Montrose, the town where my family and many friends still reside, has begun to come up frequently in conversations about the burgeoning natural gas industry as debates over “fracking” (hydraulic fracturing, a controversial method of extracting natural gas by introducing pressurized fluids into rock layers) have intensified. The northern tier of Pennsylvania sits upon the Marcellus Shale, a rock formation that contains the rich natural gas reserves that many claim are needed for American energy development. Historians and social activists in my circle were not interested in the poor farmers that became millionaires with the flick of a pen; rather, they were intrigued with the dissenters and how these locals forged communities to fight powerful corporations in saving their land and their history. I looked no further than the New York Times to see various articles on people I knew personally filing lawsuits, “occupying the wells,” and also–in ways that are interesting to me as a public historian–using the past to challenge systems of exploitation and power.

The debate about gas leases and historic properties strengthened in Susquehanna County when Cabot Oil and Gas attempted to acquire leases on lands associated with the Underground Railroad and other historic sites. (Here’s how the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission has generally responded to the connection between gas drilling and historic sites.) In antebellum America, Montrose and neighboring towns in northeastern Pennsylvania housed runaway slaves en route to Canada. The Northern Trail to Freedom, as it was called, connected Philadelphia and its outskirts to Ontario via upstate New York.

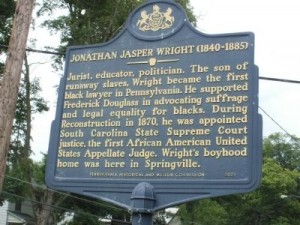

The boyhood home of Jonathan Jasper Wright in Springville, Pennsylvania, is part of the historical landscape invoked by some anti-fracking activists.

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, preservationists secured the properties on the trail and procured recognition on the National Register of Historic Places for a few of them. Many people in this region feel strongly about the importance of this past, and the thought of destroying the land for capitalist gain seemed most unnerving to many locals. When visiting a few years back, I saw many “Don’t frack our history” protest signs installed along a state route straddling many of these properties. One day, I located a small group of activists convened around the Susquehanna County Courthouse waving the same signs and passing out petitions. I took the time to talk with them and learned that many municipalities in New York, another location of natural gas interest, proposed legislation to protect historic lands and landscapes. The protestors wanted the same in Pennsylvania.

The problems in Pennsylvania escalated in 2010 when Republican Governor Tom Corbett introduced legislation that allowed natural gas companies to lease land tax-free from public colleges, universities, and K-12 schools. Obviously, public schools in the state’s northern tier found the financial incentive too great to pass up, and now most if not all of the school districts in the region allow fracking and pipeline drilling on school grounds. Many faculty members and students took to activism and demanded autonomy in making decisions that affect entire districts. Using the “Occupy Wall Street” platform, students joined “Occupy the Wells” and staged sit-ins on school properties to bring attention to what they saw as the gas industry’s calamitous relationship with the environment and society. Culling from the region’s history, these young residents recalled times when big industry entered the county and precipitately left, leaving many families in hardscrabble poverty. Local activists still remain close to their convictions that they can make a difference and hold people in power accountable.

The organizing efforts of these residents epitomize a fundamental question for public history discourse and practice, which I have written about over the past several months in the Public History Commons. That is, how can historians and publics use the power of the past to catalyze social change? In my hometown some activists, knowing they are a minority amidst a majority of citizens who sign leases and support the industry, are using public history as an organizing tool to bring historical awareness and restore pride in the area. Others are using political tactics like petitioning and protesting to promote change. It is their hope that more will join the cause and put pressure on the political systems that allow wholesale purchasing power of Pennsylvania’s historical farmland. The crusade for natural gas in northeastern Pennsylvania is not just about the destruction of historic sites; it is also about issues around environmental stewardship, gender and class stratifications, and of course, local resilience. People there either staunchly support or fervently oppose the industry, often pitting neighbor against neighbor. Locals have no choice but to look to their history for answers, resources, and inspiration, no matter what side of the debate they’re on.

I pose for Public History Commons an important question rooted in this debate: How do we bring both the diversity of opinion and the question of specifically politicized values into our public history work, especially at sites and discourses where energy development, climate change, corporate exploitation, and agricultural shifts are prevalent? In the case of my hometown, do we side with the activists using history-tactics, among other methods, or do we side with the majority that supports fracking? Is it possible to belong in the middle? I think part of the solution requires mutual dialogue among all political interests. I am amazed at how little scientists and engineers developing protocols for energy development understand the American past and how it connects to landscapes and people; likewise, historians know very little about the scientific idiosyncrasies and needs of energy alternatives. Both sides make social, political, and economical decisions not in concert with each other. If space for serious, mutual relationships and conversations can exist between people with differing opinions and values, then perhaps compromises can prevail. Finally, I see public historians acting as citizen historians in forging those dialogues.

~ Jeff Robinson is a Doctoral Candidate in the Department of History at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, focusing his research on the intersections of public history, gender, class, race, and feminism. He can be reached at [email protected].

Image sources: Gas drilling tower, Wikimedia image; Wright marker, Historical Marker Database

1 comment