In search of La Belle Vie: The Good Life. A filmmaker’s take on the Guantánamo Bay experience.

30 October 2013 – Rachelle Salinave

Guantanamo Public Memory Project, projects, social justice, media, memory, human rights, international, race

Editor’s Note: This piece continues a series of posts related to the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, a collaboration of public history programs across the country to raise awareness of the long history of the US naval base at Guantánamo Bay (GTMO) and foster dialogue on its future. For an introduction to the series, please see this piece by the Project’s director, Liz Ševčenko.

As a kid growing up in New York City in the 1980s, I was aware of an offensive perception of Haitians.The only images that the media portrayed about Haiti were negative and misleading: corrupt government, poverty, terrible rumors of Haiti being the origin of HIV, and thousands of people fleeing on boats. In school, kids would call Haitians “Boat people!” These harrowing stereotypes forced me to deny who I was in grade school just to spare the bullying.

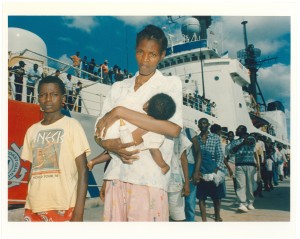

Haitian refugees. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Duke University Caribbean Sea Migration Collection, 1994

Since I was the first generation born an American, my connection to Haiti was pretty broken. I had a confusing perception of Haiti even at home. My parents always told me that we were “bourgeois” and that our story was completely unrelated to “those of peasants.” They also had a hard time associating themselves with the struggles of the lower-class Haitians that were constantly in the media. But at the same time, I believe my parents felt hurt by the mainstream media’s negative perception of Haitians because they knew in their hearts that Haiti had a beautiful history with many amazing people. When I was younger, it was these disconnections that lead me for many years to turn a blind eye toward anything that had to do with Haiti, including the Guantánamo Bay experience.

Haiti was founded on the French motto of living in a world that was filled with “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity,” turning its own motto in 1804 to “L’union Fait La Force,” which means “With Unity There is Strength.” Haiti made history by being the first Black republic to free itself from French colonialism and creating a worldwide image that slavery was inhumane and that liberty for all was a must. Ironically, years later, starting in the late 1950s, many Haitians began to flee Haiti to find liberty in the United States. Those fleeing included my parents’ generation, which were mainly the upper and middle classes. Fearing for their lives, countless of the well-educated and skilled businessmen left Haiti because of the brutality of the Francois Duvalier regime, exacerbating an already huge economic gap. After 1971 when power was passed down to his son Jean-Claude Duvalier, Haitians began fleeing Haiti by the hundreds on boats, just before Cubans began coming to the United States by boat in the 1980s. From dictators to military coups to the first democratically elected President (in 1991), Haiti has lead a politically tumultuous past that has affected the lives of many.

Haitian refugees watch from their crowded sailboat as a U.S. Coast Guard vessel approaches. Nearly 15,000 Haitians have been intercepted and brought aboard Navy and Coast Guard ships between October and December 1991. They are then transported to Naval Station, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, for temporary housing until their legal status has been determined. Photo courtesy US Coast Guard.

In the 1990s, I was still rather oblivious to the injustices that many Haitians suffered by fleeing Haiti to find refuge. In New York City, there were protests against the US government’s Krome detention center. I was a teenager at the time, and, with my parents not being so politically active, I had no idea that Krome was the holding facility in Florida where the federal government held Haitians, Cubans, or any other immigrants who made it by boat to US soil. Those people who were lucky enough to make it to the US were put in the detention center to await deportation or extradition to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

I only became more aware of Guantánamo Bay during a documentary filmmaking graduate course years later. Until then, I was like much of the general public in that I didn’t really know of the terrible treatment that was bestowed on these refugees in the States. Students at the University of Miami were asked to select a person who had been involved in the Guantánamo Bay experience. The greater part of the class chose to interview activists or survivors who told the Cuban story. It was interesting to see many of the Cuban students gravitate toward these dynamic dialogues and instantly connect since many of their parents came to America to flee the Cuban government. I undoubtedly connected with the Haitian story specifically because I was so intrigued by both the Cubans’ and the Haitians’ bravery. Hearing these stories for the first time of Guantánamo piqued my interest, and all I wanted to do was to learn more.

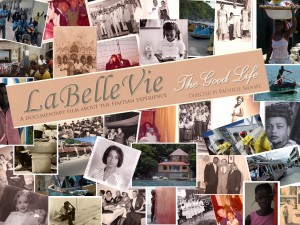

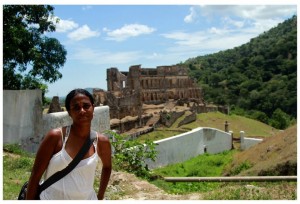

I had also been simultaneously working on my feature documentary project, La Belle Vie: The Good Life, which is a film about my own personal journey to discover my roots by discovering a new Haiti. My identity issues as a kid had inspired my work as a filmmaker to create and tell my own story and also to redefine what “La Belle Vie” (the Beautiful Life) means today as it pertains to the Haitian narrative. In learning about the history of Guantánamo as it relates to the Haitian people, I realized this vision of La Belle Vie was not so far fetched. People from all walks of life truly desire a beautiful life relative to their own reality, even if it means jumping on a boat to achieve it.

La Belle Vie: The Good Life” an upcoming featured documentary film directed by Rachelle Salnave. Photo courtesy Rachelle Salinave.

Through my research into the lives of Haitians at GTMO, I met Ira J. Kurzban. He was extremely welcoming to me and immediately gave me the legal battle story he and an entire movement of people went through to free Haitians from GTMO. Ira worked as a Civil Rights/Immigration lawyer in South Florida for over 25 years. His involvement representing the Haitian refugees and representing the former president of Haiti, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, had made him a widely recognized figure in the Haitian community. As I learned more about the terror many had to go through just to achieve a sense of freedom, I realized that all these Haitians who fled from Haiti had hearts of a lion. It troubled me to know the actual inhumane treatment people faced, which was very much hidden from the public. It pained me to think that it took me so long to learn about the atrocities that occurred in Guantánamo and the stark difference in treatment that Haitians were receiving compared to their Cuban counterparts. The US government allowed many Cubans to come to the US by granting them asylum because of the political situation in Cuba while they categorized Haitians as illegal immigrants, seeking to enter the US for economic reasons, which allowed for many Haitians to be held in Guantánamo or deported.

Ira enlightened me about the huge number of Haitian Americans around the country (but specifically in South Florida) who have been fighting for the rights of Haitians. It was this movement that had inspired him to join the fight and inevitably has changed his entire career. I was moved by his motivation to help so many innocent Haitians who were just desperately seeking a better way of life. It was extremely encouraging to know that, no matter their background and for the mere fact of protecting the civil liberties of the Haitian people, someone like Ira and so many others were fighting tooth and nail for the rights of my people. Many cases were brought to the Supreme Court and triumphed thanks to the efforts of Ira’s team. As I continue my own personal journey to discover fascinating Haitian stories, I have learned of many Haitians who were stigmatized by fleeing to the US on boats, the people who my parents called “peasants.” These very people, who just had a dream, now are proud parents of doctors, businessmen, and teachers across America.

The Guantánamo Public Memory Project is a fascinating exhibition that will give many generations an opportunity to learn about Guantánamo Bay and what people have experienced there. I feel tremendously honored to have lent my work filming Ira’s interview to the GTMO Project. It’s a great feeling to contribute to the preservation of the history of the many survivors who lived through this horrific time. The history of Guantánamo Bay has always been and will remain a great American tragedy. It’s important for people around the world, for many generations to come, to learn about Guantánamo Bay through these stories preserved through the Guantánamo Public Memory Project .

Rachelle Salnave in Cap Haitian, Haiti on the set of her documentary film “La Belle Vie: The Good Life” Photo courtesy Rachelle Salnave.

As for the many amazing heroes who risked their lives for the sake of liberty or just dreamed about what “La Belle Vie” would feel like in America, I am a proud Haitian today because of their courage.

For more information about The Haitian Guantánamo Bay Experience : The Legal Journey- Click https://vimeo.com/39612144

For more information about La Belle Vie: The Good Life: https://vimeo.com/40761802

Marine LCPL Donald Kenley, Camp Lejuene, North Carolina, carries one of the Haitian refugee children at the Camp McCalla tent facilities on the US Naval Base at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba. More than 14,000 refugees attempted to reach the United States by boat and were picked up by the Coast Guard in international waters and transported to the base at Guantanamo Bay.

Photo credit: Courtesy of US Department of Defense, July 1, 1992

~ Rachelle Salnave, born in Harlem, New York, has managed to balance an extensive range of professional experiences working with key players in the film and the music industry. For over a 10-year span Salnave has documented her community by creating a film about the gentrification of Harlem, called “Harlem’s Mart 125: The American Dream” which has toured film festivals, universities, and community organizations around the country. “Harlem’s Mart 125” won “Best Documentary” at the 2010 African World Documentary Film Festival in St. Louis.

Salnave is currently working on two documentary films: “La Belle Vie: The Good Life,” a documentary about her personal Haitian experience and “Heavenly Nut,” which looks at one family’s mission to save the environment by planting macadamia nut trees. Rachelle Salnave is based in South Florida.