Making home front connections

17 November 2022 – Allena Berry and Suzanne Fischer

What exactly defines a home front? With that question, the U.S. World War II Home Front working group began our first meeting. Very few visitors to WWII sites in the United States, especially those who come from non-white communities, see their history as home front history.

Too often, visitors come to our sites with a particular image of the home front in mind—generally, some version of the tough woman, usually white, who stepped into factory work to support the war effort domestically. Our group is made up of a range of practitioners who work in varied settings, and each wants to help build a more expansive and inclusive definition of the home front as it pertains to World War II in the United States.

The “Georgia Goes to War” exhibit at the Museum of History and Holocaust Education at Kennesaw State University in Kennesaw, Georgia.

In this working group, we aim to challenge that narrative at our sites.

The National Council on Public History (NCPH) and the National Park Service (NPS) have been collaborating on several projects to research and share histories of the World War II Home Front. One project is a three-year Working Group dedicated to promoting discussion of home front interpretation among NPS sites and other organizations who tell or would like to tell home front stories. Our group is made up of the following individuals:

Dr. Jadelyn Moniz-Nakamura, Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park

Leslie A. Przybylek, Senator John Heinz History Center

Tom Leatherman, Pearl Harbor National Memorial

Adina Langer, Museum of History and Holocaust Education, Kennesaw State University

Gretchen Stromberg, Rosie the Riveter / WWII Home Front National Historical Park, John Muir National Historic Site, Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial, Eugene O’Neill National Historic Site

Niki Nicholas and Matthew Klein (current working group members), Kris Kirby and Becky Burghart (former working group members), Manhattan Project National Historic Park

Since our first meeting in February 2022, the WWII Home Front Working Group has engaged in conversations that span the philosophical, theoretical, and practical dimensions of our historical practice. These conversations have helped this working group establish the rapport and relationships that will be necessary to carry on our work in the next two years. Specifically, we are looking to develop a network of public and private sites interested in telling a broad story of the WWII U.S. home front. In particular, we want to connect NPS sites with each other and with other institutions across the country. Ultimately, we hope that the relationships we develop could lead to the development of a clearinghouse for research, collaboration, and, potentially, content sharing.

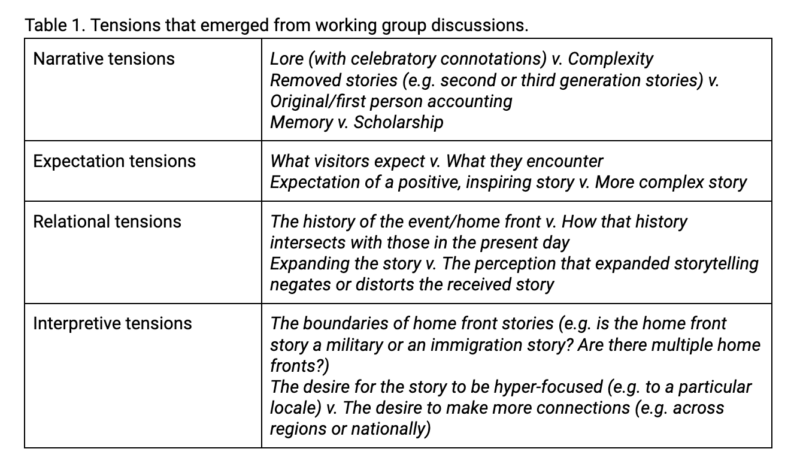

Table 1: Tensions that emerged from working group discussions. PDF version available here.

One of the most fruitful outcomes of our conversations has been sharing across sites in an informal way. These moments of sharing have allowed us to identify what we have been calling generative tensions (listed below). We define these issues as tensions because there is not a clear way to compromise between the stories that, say, exist in the archives already and the stories that may not have been collected in the archives but that have been passed down through family over the years. We found these tensions helped us characterize some of the challenges we were facing across sites and to begin thinking creatively about how to work ourselves out of the binary these tensions represented.

Some key examples help highlight these tensions. We have seen, across our sites, that there is an expectation from visitors to learn about women in the home front workforce, as the above-shared experience of what defines the “home front” attests. Some visitors are surprised, and even disappointed, when we talk about other home front stories, such as the experiences of the LGBTQIA community, Japanese incarceration, expansive immigration and migration stories, and experiences of racial segregation and injustice. Some visitors also see discussions about topics like women’s resistance to taking on defense jobs; workplace discrimination against women focused on race, age, or marital status; or challenges surrounding aspects like childcare as revisionist complications to more heroic narratives.

Furthermore, there has been a shared sense across multiple sites that stories about industrial defense production, technological innovation, and scientific achievements on the home front have a public expectation to be primarily celebratory symbols of U. S. corporate ingenuity and the tools of “American Victory.” How many sites proudly identify themselves as “Arsenals of Democracy”? We desire to tell positive stories, but we also see the benefit of complicating those narratives with the real experiences of workers in those plants, exploring tensions that arose within labor organizations, and asking larger questions about the sometimes complicated implications of technological outputs that carried negative as well as positive outcomes.

In short, we have, in our first year, experienced the need to tell multiple stories about multiple home fronts and bring our visitors along in that process.

As our conversations continued, we saw that the creation of a sustained network for the purposes of professional development and resource sharing could be a way for each of us to navigate the aforementioned tensions and find new ways to engage the public in this critical work. If our past conversations are any indication of where the next two years will bring us, we are looking forward to more thoughtful engagement from this group around interpreting, and presenting those interpretations, to the public.

~Allena Berry, Ph.D., is a lecturer in the Department of Teaching and Learning at Peabody College, Vanderbilt University. She teaches future history educators with a focus on the literacy practices necessary to engage young people in the discipline.

~Suzanne Fischer is an independent interpretive planner and exhibit developer based in Lansing, Michigan. Reach her at [email protected].

The National Park Service can’t possibly tell the complete picture of the “Home Front of World War II. The Home Front story which has to include the stories of such men and women as my Father John Wesley Cowles who was an Electronics Repairmand in the 1920s and the 1930s, who were unable to qualify for duty with the Armed Forces. He worked as a Civilian Electronics Technician with the Army Air Corps assigned to a particular B-17 Bomber Squadron during their training at air bases in the Northeast and Dyersburg Tennessee. His job was to maintain the Radio and Guidance systems abosrd the B-17 aricraft assigned to the unit. My mother Hortense Parker Cowles traveled with dad and she had attended Arkansas Agriculture and Mechanical School in Jonesboro, Arkansas studying Office courses such as Short Hand Dictation, Typing, and Filing. At each of the bases that my dad was assigned to mom would work in one of the base adminiatrative offices. Their story is one of hundreds of including one of my Uncles who was stationed at Aerial Gunnery School in Tampa, Flordia and his wife drove large personnel transport trucks. Then there were War Bond Drives, the Home Garden Program, the Tire Recycling Program, Glass Bottle Recycling Program that whole families participated in. There are various City and County Historical Societies along with the local VFW and American Legion posts that maintain records of these activities. There would need to be a Home Front NPS in every town in Amreica.