Guantánamo Public Memory Project: Three experiments in public engagement by public history at Arizona State University

27 December 2013 – Nancy Dallett

Editor’s Note: This piece continues a series of posts related to the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, a collaboration of public history programs across the country to raise awareness of the long history of the US naval base at Guantánamo Bay (GTMO) and foster dialogue on its future. For an introduction to the series, please see this piece by the Project’s director, Liz Ševčenko.

Chain link fence served as the substrate for the Guantánamo Public Memory Project exhibition at the Phoenix Public Library. Photo credit: Nancy Dallett

With the conclusion of the Guantánamo Public Memory Project @ Phoenix Public Library, those of us who helped plan and program the traveling exhibit now can pause to take stock of the experience. We have confidence that we presented the exhibit as aesthetically and compellingly as possible, such as by using chain link fencing as the structure for hanging the panels. My attention for this review, instead, focuses on three ways we experimented with partners and programming.

Our first fundamental decision about staging the Guantánamo Public Memory Project in Phoenix was to find the best venue. First choice: The Phoenix Public Library. In its 20 years of service, the Library has grown in stature both architecturally and in prominence to the communal life of the city. It is the most public of places in this highly privatized city, with diverse programming to attract all ages every day of the week. The library staff was immediately receptive to the project and the collaboration, and we began meeting monthly a year in advance of the arrival of the packages for Phoenix installation. We learned of the library’s nuanced understanding of the interests of their users, effective methods to publicize events, close working relationships of staff to service exhibits and programming, and their willingness to experiment with new ideas and formats to adopt new techniques to attract new audiences.

Together we decided to experiment in three ways to widen the topic of Guantánamo to attract Phoenix audiences which, the library staff warned us, would not be drawn to the topic unless we associated it with more appealing Arizona-related topics. We decided to broaden the topic, approach, and format.

1. We chose to widen the topic of Guantánamo to include comparable historic and contemporary events in American history with Arizona connections. We chose to focus on the World War II hysteria after the bombing on Pearl Harbor that led to Executive Order 9066 and to Japanese Americans being sent to internment camps throughout the West, including camps in Arizona on Native American tribal reservation land. Speakers and artists explored the last 60 years of history and collective meaning-making, including apologies and reparations. Although inadequate, these symbols of national introspection and admission of errors have done much to restore a sense of honor within the Japanese American community who suffered the degradation and humiliation as well as within the wider American community on whose behalf these internment camps were conceived and operated. One of our events at the library featured Wendy Maruyama, who spoke about her “Tag Project,” then on view at the Arizona State University Art Museum. The Tag Project helped audiences to sense the similarities between the push for Japanese internment and the overreaction following September 11 that led to secret prison sites and an increase in executive powers to fight the “War on Terror.” Cross-promotion of the Guantánamo Public Memory Project with the Tag Project, for which Maruyama created an identity tag for every Japanese American interned in the major camps, provided fertile ground for exploring the concept of public memory.

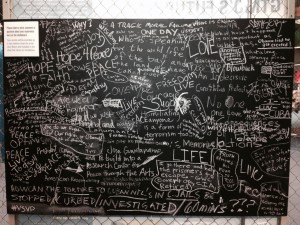

2. We chose to open doors to public engagement with the topic of Guantánamo through public art. We secured funding and commissioned a public artist who created the “memory shard” art installation. Acting as a scribe for public sentiment, she collected phrases, ideas, messages, detainee names, quotes, and hopes from people who wrote on the exhibit chalkboard or offered their inscriptions at the events, and she then transcribed these notes onto clay shards. She fired the clay shards and gave people wire to attach the shards to the chain link fence. Through this participation, integration, and hands-on process, visitors became “linked” with the exhibit. They made connections with one another and bound themselves to the situation at Guantánamo and the conversation about the situation. The continued conversation further invigorated the public process and contributed to the shard-by-shard growth of the installation over the life of the exhibit. We encourage partners and sites to adopt this aspect of the exhibit, which made it active and engaging at a personal level. The 231 clay shards are a testament to our twin goals of combining good public art with good public history.

3. Finally, we chose to experiment with new formats to engage public audiences. Perceiving a general fatigue with single speakers and panels talking “at” audiences, we experimented with a new format: the Human Library Experience. Popular throughout Europe, but little known in the US, the Phoenix Library was interested in using this method to promote one-on-one dialogue in which people serve as “books” and others as “readers” for 15- to 30-minute private conversations. Our “books” included a person who served in the military at Guantánamo in the 1960s and now is active in Veterans for Peace; a person who served as a guard in 2003 and through that exposure to Muslim detainees became familiar with and embraced Islam, which led to his discharge from the army; a person who was held in detention in Iran for many years; a person who provides legal assistance for immigration detention cases; and a person who rafted from Cuba and was detained at Guantánamo for over a year, during which time he taught art and created gallery spaces, ran a newspaper and a radio show, and eventually was released into the US and settled in Phoenix. The Human Library experience scored very high on public evaluations, and the Library will begin offering Human Library experiences regularly.

With each of these attempts to broaden interest, collaborate with new partners, and experiment with new formats, we stretched our previous notions of how to promote programs on difficult subjects to make them more attractive to the general public. We also created new partnership potential for future projects, and we expanded our repertoire of programming formats beyond the traditional lecture format. ASU Public History students were vital in the planning, exhibit installation, programming ideas and execution, publicity, experimentation, and evaluation. We look forward to sharing our experiences and advice with upcoming venues for the Guantánamo Public Memory Project and learning from other public history programs as they push us to engage wider publics.

~ Nancy Dallett is the Assistant Director of the Public History Program for The ASU School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies.