Reading the artifact: The story in the archives

07 October 2013 – RASI 2012

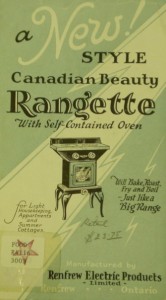

The brochure that accompanied the mystery stove. (Source: Canada Science and Technology Museums Corporation, No. L11201)

Read Part I of this series here.

On the second day of the Reading Artifacts Summer Institute (RASI), we received the artifact accession files. Although our physical examination of the stove had proven effective, artifacts need some help to speak. Material cultural historians have shown the benefits of (re)connecting objects to their historical contexts by undertaking a process of “thick description,” combining the use of written sources with material ones.[1] We eagerly anticipated what the accession file could tell us about the stove’s origins, manufacture, and targeted audience.

From the documents, we learned that this stove was a Canadian Beauty Rangette, built in the early 1920s by the Renfrew Electric Company from Renfrew, Ontario, and donated to the museum in 1981. Many questions still remained, but these new pieces of information helped focus our investigation when we accessed the Canadian Science and Technology Museum’s (CSTM) Archives and Library and later, its expansive storage facilities. The CSTM’s storage warehouses, in particular, proved useful because we were able to photograph and retrieve similarly styled household appliances for comparative purposes. The objects we found demonstrated that a wide range of domestic appliances was available to the household consumer in the early twentieth century, and that new materials, new production processes, and the introduction of electricity had reshaped the layout and design of most kitchens.[2] The popularity of the new “laboratory”-style kitchen and an emphasis on cleanliness and efficiency meant that our Victorian-style stove seemed out of step with the sleek “futuristic” design we observed in all the bigger ranges we found.

The documentary sources we discovered at the CSTM’s Library and Archives were also valuable to our investigation. Aided by the archivists, we found a brochure for the Canadian Beauty Rangette (above). From the pictures in the brochure we discovered that our Rangette was largely intact, except that the backsplash for the stove-top was missing and the oven door was originally finished in blue enamel, rather than its current black. We also learned that the Canadian Beauty was advertised as an appropriate appliance for “Light Housekeeping, Apartments and Summer Cottages,” and that its self-contained oven was capable of “cooking a medium size roast or two pies or cakes at the same time”![3]

The brochure suggested that the targeted user for the Rangette was the housewife. Not only did advertisers contend that the Rangette was economical on power and “so much Safer and cleaner than Coal oil or gas” but they also noted that the Rangette had “a beauty of design and finish that makes the kitchen more attractive.” The stove would make “Cooking a pleasure to the housewife during the hot weather,” a point underscored by the poem on the back of the brochure:

A woman with plenty to do,

Had a holiday all summer thro’

She bought a Rangette,

From then on you bet,

She was Cool and Contented,

Are you?

Detail of the stove’s cabriole legs. (Source: Canada Science and Technology Museums Corporation, No. 1981.0040)

This poem reflected the era’s gendered assumptions of household skills and tastes. In discussing material culture, Jules David Prown has argued that the analysis of style is central to cultural understanding.[4] The curved lines of the Rangette’s cabriole legs may have appealed to a feminine aesthetic that found the straight, rigid lines of other more modern pieces too harsh or unappealing.

Detailed readings of the documentary evidence for the Canadian Beauty Rangette also revealed a great deal about how sophisticated advertising campaigns of this era exaggerated the attractions of domestic appliances and argued their necessity.[5] For instance, the Rangette’s brochure emphasized the clean countertop made of “genuine pearl gray vitreous porcelain” and the stove being “economical on power,” and “safer and cleaner than gas.” However, many electric cookers and hot plates from this period were burdened with numerous problems, including slow, unreliable, and energy-hungry elements. On the other hand, a market had already been captured by robust cast-iron ranges and gas cookers, which were built to last.[6] The Canadian Beauty Rangette’s combination of a cast-iron range with polished enameled counter surfaces can thus be explained as a marketing ploy by the manufacturers. The stove was marketed as the ideal modern household cooking appliance, combining the efficiency and cleanliness of modern electricity with the assured reliability of a cast-iron stove.

The brochure also made us aware of how important artifacts are as historical evidence. For example, the brochure explained that the Rangette was ideal for a housewife and that she could bake a medium-size roast or two cakes or pies at one time. However, one look at the small oven led us to immediately question this exaggerated assertion. Furthermore, while the Rangette was targeted at the housewife, the cooking limitations of the appliance suggested that it was more likely to be used in a bachelor-style apartment or kitchen with limited space. Perhaps the newly married housewife could have made do with this stove, but it is unlikely that it would have satisfied a wife and mother cooking for a family. And even though the brochure explained that it was suitable for the summer cottage, we had already questioned how many cottages in the 1920s had access to electricity. More likely this stove was used in an urban environment. (Indeed, we later found out that a similar stove had been used in the lunch room of a taxi-cab dispatch center.) Additionally, the thin metal from which it was made and the relatively high voltage capacity of the oven would have allowed for a significant amount of heat to escape while cooking, leaving users less “Cool and Contented” than the advertisement claimed.

“Canadian Beauty” product booklet. (Source: Canada Science and Technology Museums Corporation, No. L10215)

We were also intrigued with the name of the object, and we speculated that the name “Canadian Beauty Rangette” reflected the nineteenth-century tradition of appropriating Canadian national symbols like the maple leaf or the beaver for marketing purposes.[7] The product brochures emphasized that Canadian Beauty appliances were “purely native products,” marketed towards those “whom home and country have any meaning, and who can appreciate Canada’s prominence among the electrically endowed countries of the world.” While the company insisted that their products had succeeded “without appeal to sentiment, on a, strictly value-for-dollar basis,” clearly it was profiting from the Canadian name and nationalistic imagery of early twentieth-century English Canada.[8] But how popular was the Canadian Beauty Rangette? It would appear that despite its sophisticated marketing campaign, the Canadian Beauty Rangette did not prove to be a big seller. By 1926 product lists produced by Renfrew Electric (above) show that this small stove had been discontinued after just a few years, replaced by larger rangettes which catered to the greater market.[9]

The third and final post in this series will follow with the presentation of our artifact findings to the RASI course participants and museum staff.

~ Laura A. Macaluso is a doctoral candidate in the humanities program at Salve Regina University in Newport, Rhode Island, United States. Jodey Nurse is a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Guelph in Guelph, Ontario, Canada. Emma O’Toole is a Government of Ireland doctoral scholar at the Faculty of Visual Culture, National College of Art & Design, Dublin,Ireland. Alex Souchen is a doctoral candidate in the Department of History at Western University in London, Ontario, Canada.

NOTES

[1] Bernard L. Herman, The Stolen House (Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 1992), 4, 11.

[2] Penny Sparke, Electrical Appliances (London & Sydney: Unwin Hyman, 1987), 21.

[3] Renfrew Electric Products Limited, “A New! Style Canadian Beauty Rangette With Self-Contained Oven,” Catalog No. L11201, Canada Science and Technology Museums Corporation.

[4] Jules David Prown, “The Truth of Material Culture: History or Fiction?” in History from Things: Essays on Material Culture, eds. Steven Lubar and W. David Kingery (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993), 4.

[5] Christina Hardyment, From Mangle to Microwave: The Mechanization of Household Work (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1988), 177.

[6] David De Haan, Antique Household Gadgets and Appliances, c. 1860 to 1930 (Dorset: Blanford Press, 1997), 7.

[7] See Paula Hastings, “Branding Canada: Consumer Culture and the Development of Popular Nationalism in the Early Twentieth Century,” in Canadas of the Mind: The Making and Unmaking of Canadian Nationalism in the Twentieth Century, eds. Norman Hillmer and Adam Chapnick (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007), 134-58.

[8] Quotes from: Renfrew Electric Products Limited, “Toast as you have never known it before,” Catalogue No. L10214, Canadian Science and Technology Museums Corporation Library.

[9] Renfrew Electric Products Limited, “Canadian Beauty Majestic Beaver Appliances,” Catalogue No. L10215, Canadian Science and Technology Museums Corporation Library.

2 comments