The AHA on the path to public history

09 March 2015 – Rob Townsend

The past of public history can be traced along many different paths, but at least one runs though the American Historical Association. My interest in this question was first shaped at a lunch for the National Council on Public History at the AHA’s 1997 meeting. Much of the discussion circulated around two key issues–a catalog of personal slights by academics and an argument that the AHA was established for academics and making a false claim of authority over the entire history discipline.

In probing how and why there seemed to be this deep gulf between academics and public historians, the causes seemed to recede ever further in the past. Looking back at the papers of the early AHA, for instance, there were quite a few people circulating around in the leadership who looked rather like public historians: Reuben Gold Thwaites, the head of the Wisconsin Historical Society; Solon Buck, of the Minnesota Historical Society and later the National Archives; and Waldo Gifford Leland, secretary of the AHA and an early leader in the development of archival standards. Even some of the more traditional academics, such as J. Franklin Jameson at Chicago and Lucy Salmon at Vassar, were actively promoting documentary editing, historical societies, and other activities now widely recognized as public history.

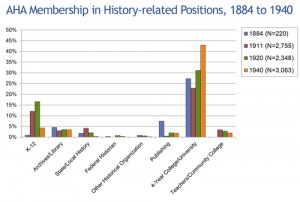

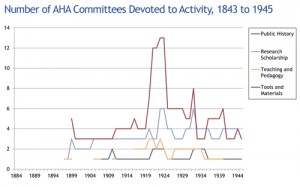

The AHA’s engagement with these activities went well beyond its personnel. Through most of its first 60 years as an organization, there were more committees and groups assigned to projects outside of academia (e.g. the Historical Manuscripts and Public Archives commissions and the Committee on Radio) than there were to projects focused on the publication and development of traditional scholarly research. These projects focused the collective efforts of senior academics, documentary editors, government employees, and others in an effort to preserve and disseminate history for a wider public. Just as important as what the AHA was doing is who was doing it. In the period before 1910, it was taken for granted that distinguished faculty from prestigious universities would be active participants in all of these activities. It was only after the mid-1920s that high-level faculty absented themselves from this work, and specialists were brought in to serve on increasingly marginalized projects.

Tracing the history of where all those activities and those engagements went, the whole story becomes increasingly complicated. It is not just a simple story of the academics turning their backs on other groups and activities. Instead, it seems a common language and shared principles about what constituted good “scientific” history became increasingly complicated, driving wedges between the emerging professions in the discipline.

Part of the change that took place was the development of new technologies. The index card and the typewriter, for instance, sped up the pace and production of scholarly research and raised expectations for productivity. The photostat machine and the microfilm reader created similar disruptive changes in the archives and historical societies–creating new employees and relationships between the societies and libraries. Copies of materials even became a sort of currency of exchange between the organizations, as they set up networks to share and track the resulting materials. At the same time, the number of institutions and employees at various levels were undergoing rapid expansion and differentiating into a growing variety of professional activities as their work was shaped by increasingly technical standards and expectations.

The resulting networks had secondary effects. As archivists and historical society leaders and employees began to set up new systems and develop related standards, they established their own perceptions of best practices and deepened their work in ways that even the most attentive scholars found difficult to track or understand. As a result, the academics were increasingly shut out of conversations that were growing esoteric in their own ways.

Thinking just in terms of AHA meetings in the 1920s, even though a majority of the members of the AHA were not employed in academia, the meetings were now offering four or six or ten simultaneous sessions primarily on specific–and increasingly narrow–topics of history. These sessions competed for attention with a much smaller number of sessions about emerging practices of documentary editing and important new primers on archival practices coming over from Europe. Slowly, the conversations became deeper and more technical on all sides. The people participating in each conversation became more actively and rigorously engaged with an ever smaller sphere of people. These communities were growing larger in terms of numbers but more tightly contained in terms of the standards and language they used to assess each other’s work.

Reinforcing these divisions, caricatures of academic historians as separated from the realities of the world began to gain significant cultural traction around this time. As these settled into popular perception, these caricatures were deployed by many other history professionals, who cited the disengagement of the academics as part of the reason for forming separate historical organizations (the Society of American Archivists, American Association for State and Local History, and ultimately the National Council on Public History).

All that may seem obvious when the story is laid out that way, but the relationship between academic historians and public historians certainly wasn’t clear from 1884 looking forward. I’m not sure it was any clearer from the perspective of 1997 looking backward either. I left that NCPH discussion, and quite a few conversations with public historians since, with the sense that the problem was all with the academics–instead of differences that separate our shared interest in the past into the particular ways we do our work and judge the work of others. As someone who worked at the AHA for 20 years without a PhD, I fully understand the particular attitudes of academics that public historians find so infuriating. Believe me. But I’ve come to see the attitudes and the larger challenges they represent as arising from patterns deeply rooted in a history that we all share and need to understand more clearly if we are to work together in the future.

~ Robert B. Townsend oversees the work of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ Washington office and the Humanities Indicators. Prior to the Academy, he spent 24 years at the American Historical Association, rising from an editorial assistant to deputy director. He is the author of History’s Babel: Scholarship, Professionalization, and the Historical Enterprise, 1880–1940, which received the 2014 NCPH Book Award.