The Art of (virtual) gathering: Considering audiences with purpose and intention

05 March 2021 – Priya Chhaya

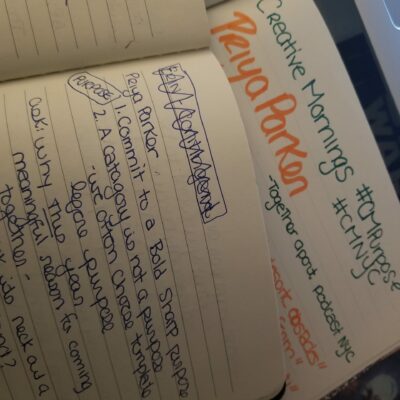

The author’s notes from the Art of Gathering in April 2019 and notes from Creative Mornings that featured Priya Parker in April 2020. Photo credit: Priya Chhaya

For the last fifteen years I have worked as a public history digital content creator. Much of my work has been learned on the job as I engage with the tools and technologies of multi-disciplinary storytelling—and more recently, consider how technology facilitates community engagement with history in both public and intimate settings. In most cases, especially in terms of the programs I sought out—it was the in-person experience that often superseded the online visitor.

However, all that changed in early March 2020 when we all had to become digital-first individuals, organizations, and programs. For those institutions that had already invested time and energy into developing robust online programming the transformation was easy; for others, it involved an unexpected pivot, resulting in a barrage of programming with uneven results.

I write these words acknowledging that we were all mired in—and still are—a situation where many of our institutions were driven by pandemic realities. Confronted with an unexpected drop in revenue, cultural organizations made rapid changes to both staffing and budgets (forever highlighting the fragility of the field). These decisions resulted in an expectation that remaining staff would pick up distinct skill sets related to education, content development, and delivery in order to produce quick, high-quality content.

In a lot of ways, we were all trying to do our very best to survive, and every program was created in the name of visibility and relevance. Non-profit and professional institutions pulled together webinars in the blink of an eye as a way to provide resources, education, and information about financing, employment, virtual programming, and more. Museums and historic sites developed virtual tours, object lessons, and individual lectures to keep the history and value of these sites front and center.

But sometimes, more isn’t better.

Prior to the pandemic I read The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why it Matters, by Priya Parker, a trained facilitator and negotiator. When everything shut down, she was one of the first speakers I heard clearly describing how best to approach the transition from physical to virtual. Specifically, I considered over and over again her tenet on beginning every program planning not only with purpose and intention but also a clear vision of what would make the event successful in line with whatever technology we plan to use.

In hindsight—which is always 2020, to allow me this pun—while all of this content felt important and necessary, as I look back at the many webinars I attended (some of which I helped create) it is evident that in our haste to fill the void we charged forward without that clarity of purpose or consideration of the capacity of our audiences to engage our information in digital spaces. With that in mind, I will highlight two examples of virtual programming—outside of the traditional public history sector—that I feel were successful in considering the both audience and platform as part of their work.

Building Community at Creative Mornings

For those of you who don’t know, Creative Mornings is a once-a-month gathering that started in 2008 by Tina Roth Eisenberg as a way to bring the New York City creative community together for breakfast and an inspirational conversation based on monthly themes. Today these mornings take place in over 230 cities worldwide and bring together creatives from a variety of fields to consider the role their work plays in the wider world.

For me, a central piece of Creative Mornings is community. In person, it starts with coffee and conversation supported by local businesses, where talking to strangers is encouraged, and—in DC where I am from—we are almost always asked to say hello to someone we’ve never met before once we sit down. It was this collective connection that really elevated these events beyond a simple lecture or presentation.

When the pandemic hit, it was evident from the beginning that things had to change. They brought in Priya Parker, who asked them to consider the purpose of Creative Mornings. The resulting strategies were born out of risk taking and innovation but what also (from the outside) felt like careful consideration and planning.

This involved things like leveraging the Zoom chats to encourage connection and conversation by asking the audience questions and having them share answers at the same time, or taking people off mute. Then, in order to provide the more intimate setting of talking over coffee and pastries, Creative Mornings embraced, early on, the function of small groups so we could build one-on-one connections with individuals across the world. Where we were became part of the conversation, helping to build a virtual community. The theme of “Spectrum” brought another favorite technique to create connections. The creators released a series of virtual color backgrounds for the audience to use to reflect their mood—and when everyone was in gallery mode you saw synergy with others who felt the same way.

So yes, while we still got inspirational talks (that as time went on moved more and more away from power points towards becoming a dialogue), that sense of creative energy was sustained in a way that elevated moods. The key was not to replicate the in-person experience but to embrace the new while keeping the spirit of the broader event.

The Show Must Go On: Inspiring and Connecting with Intention Through Theatre

Last year, one of my coping mechanisms was to become deeply engaged with the work of William Shakespeare. Like so many, my local Shakespeare theatre (one of many fantastic ones in the DC area) pivoted fairly quickly to a series of digital programs under the banner Shakespeare Everywhere.

One particular event that occurred weekly on Wednesday nights was the Shakespeare Hour, which centered on either a single play or a broader theme. While many topics were pre-determined, the company was able to pivot within the established format to create connection and relevance to what we were experiencing in the wider world.

On the surface these felt like a standard online presentation: two to three speakers, a moderator, and an online chat. The critical difference from many of the other events I attended was how clearly the Shakespeare Theatre Company defined and established the intention and purpose, and consequently showed, week after week, how important and connected their work was to their community and beyond.

Shakespeare Hour also embraced a casual, conversational tone, something I often found lacking in other digital programs.

No matter the topic, the moderators created an intimate conversation between the viewer and experts in the field. Each session ended with a Shakespeare reading—one that tightened the connection between the attendee and those who had been taking us on an hour-long intellectual journey.

My set up to watch the live stream of Romantics Anonymous at the Bristol Old Vic. At about this point in the broadcast they had to halt the show and restart to deal with some sound syncing issues in the stream which gave it an element of tension you get with in-person live theatre. Photo Credit: Priya Chhaya

At the start of this piece, I mentioned how many of the webinars we developed in 2020 were intended to convey that our work was relevant and essential. One way theatres have been successful in demonstrating relevancy is by building transparency into the purpose of their online content. When we step into a physical theatre, we often fail to see the puzzle pieces that put a production together. During the pandemic, as virtual theatre has become all the rage, some productions have seized the opportunity to show everyone who was involved with the event. This was the case with a live streaming of Romantics Anonymous by the company Wise Children at the Bristol Old Vic. Each production took a moment to acknowledge the people behind the theatre, a reminder that so much and so many lives go into the bringing of this art form to fruition. To show us, truly, at a time when we are isolated in our homes, what goes on behind the curtain. For public history, transparency is equally important. It reveals not only the work that goes into the production of our programs but also gives awareness and credit to all who are involved with its development.

What is Your Purpose?

Back in April of 2020, during her presentation for Creative Mornings, Priya Parker emphasized the importance of an unwritten social contract between the audience and the program creator—that every person attending an event, virtual or in-person, comes with an expectation of what they are about to experience.

What she makes clear, however, is that it is up to us, as the content creators, to lay out the ground rules. We ought to let our audiences know what to expect up front, and then—even as we take risks with format, tone, and methodology—use this purpose as our touchstone for everything from the invitation/registration links to the collection of post-event feedback.

And so, as we head into what may well be another year of socially distant/online gatherings, I would like to take that one step further. As individuals who work in cultural and historical institutions and spaces, we need to make sure that we as creators are clear on what we want to accomplish from the beginning. To ask not what this program is about, but rather (paraphrasing Parker), why we are producing this content in the first place.

I recognize that there is a very real labor element that goes into some of these activities, not to mention a paucity of time to do the deep necessary thinking we need. However, I still advocate taking a few minutes as part of the planning process to clearly identify overarching goals for each event. Finding creative ways to build community and connection, with purpose and intention built in from the beginning, is essential to any programming we do going forward.

~Priya Chhaya is the Associate Director of Content at the National Trust for Historic Preservation.