Pictures to dream with: A public historian in the nursing home

19 June 2015 – Emily Oswald

Rignes Brewery, 1926, by Anders Beer Wilse. Photo credit: Oslo Museum oslobilder.no

“What’s that? Horses?” the elderly man with the eye patch said loudly, in Norwegian, as his neighbor described the picture on the screen. “I remember when things were delivered by horse carts.” He didn’t elaborate and perhaps the memory ended there. But I thought of him months later when another nursing home resident told me about her grandmother. The previous evening, we had looked at pictures of Norwegian kids on vacation, and she explained the photographs made her think of spending summers at her grandmother’s home in the countryside. The photographs had clearly lingered in her mind. “I loved it there,” she said, “There were horses and cows and animals.” I wondered then whether the man with the eye patch had gone back to his room that cold evening in February and dreamed of horses on the streets of Oslo. He hadn’t even seen the picture, but hearing about it was enough to elicit memories of that time before.

Since this past January, I’ve been going to a senior center on the east side of Oslo every other Tuesday evening. I bring a PowerPoint presentation and my best Norwegian grammar and sit down with men and women in their 70s and 80s. We spend about an hour together, looking at historic photographs projected onto the wall of the center’s cafe. Together, we’ve flipped through images that document the working lives of Oslo residents; photographs of the city’s schools, breweries, and newspaper kiosks; images of Oslo in winter from the 1890s; and in spring from the 1970s.

Newspaper kiosks at the Sentrum metro station, 1977, by Leif Ørnelund. Photo credit: Oslo Museum oslobilder.no

I’d been volunteering at the senior center for a couple of months before I approached the activities director about doing something with historical photographs. There was an online database I’d been eyeing, and I wondered what their needs for programming were. “Could you come in the evenings?” she asked immediately. “We’re happy for just about any kind of evening program. It’s easy for the conversation to get stuck on what they didn’t like about the lunch menu.” A goal had been articulated, and a “program” was born. We called it “Oslo i Bilder”–“Oslo in Pictures”–and agreed that I would come twice a month.

Senior centers, nursing homes, and perhaps even hospital rooms are places public historians should think more about. These are places where resources at our disposal can, with a modest investment of time, meet important existing needs. For the senior center in Oslo, the need was clear: a volunteer-run evening program that would give residents something to think and talk about besides the food. And my resources were pretty obvious, too: I knew about and was interested in historical photos, and I had time on my hands while I was learning Norwegian.

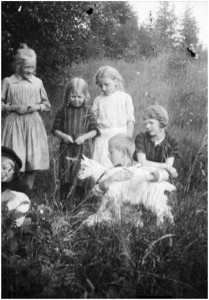

Unknown children, c. 1905 – 1910, by Reidar Holtvedt. Photo credit: Oslo Museum oslobilder.no

Three specific resources, in addition to my time and the good will and open-mindedness of staff at the senior center, make Oslo i Bilder possible: a well-cataloged database of historical photographs; easy display technology; and an interpretive framework that is meaningful for my audience. The database, oslobilder.no, makes thousands of historical photographs available online. Each image is extensively cataloged with cross-referenced information, including location, date, and subject, from retail window displays and tram cars to Crown Prince Harold’s marriage in 1968. If I have a theme in mind, making a presentation of 40 or 50 photographs generally takes about 90 minutes. Production value is minimal: no graphic design, no mounting, no hanging: I just show the slideshow using a projector and laptop. The speed and ease of production means that we can talk about a different set of images each week and still keep my prep time to a level that makes sense for a volunteer gig.

The third resource is the one that draws most on my public history training. It’s the ability to curate and apply an interpretive framework so the photographs mean something and make sense. The importance of interpretation may be what I find most exciting about Oslo i Bilder. It’s not enough that the pictures were available and well-cataloged online, or that the senior center has a good projector and an excellent Internet connection. To give people something to talk about, the photographs need to be interpreted, even minimally, and their viewing facilitated. Someone had to choose pictures that might prove interesting or evocative or engaging and decide to talk, for example, about snow in February and summer vacation in June. This interpreting and facilitating is work that many in our professional community are well-positioned to do, from emerging professionals like myself, looking to bolster our portfolios while we apply for full-time work, to executive directors of local historical societies who want to get more mileage out of a major digitization project.

Playing on the sidewalk in front of the Parkteatre Cinema, 1958, by Ottar Gladtvet. Photo credit: Oslo Museum oslobilder.no

Not everyone in a nursing home suffers from memory loss, but the prevalence of dementia adds a poignant and compelling layer to this work. I’m excited and terrified by the “dementia epidemic” Lisa Eriksen writes about in two recent posts on museum programming for the elderly. In the next decade, the Alzheimer’s Association estimates the number of people 65 and older with the disease will increase by 40% to seven million people in the United States.[i] As Erikson points out, “people with memory problems will be visitors at your museum whether you know it or not…as public institutions with a mission of community service, how do we serve this population?”

Public historians won’t find the medical cure for Alzheimer’s. But without changing the fundamentals of what we do (interpreting the past and facilitating meaningful engagement with audiences, historic objects, images, and places), we can make a difference for people with dementia and other problems that may come with age. Like a growing number of art museums, our resources can contribute to their well-being and that of their caregivers. We can help to give them something to think and talk and dream about besides the food.

~ Emily Oswald is a 2013 graduate of the University of Massachusetts Amherst Public History Program. Read more about Olso i Bilder in her recent post for the UMass blog, Past@Present. Emily moved to Norway for her husband’s job in August 2014. It’s been darker–and more fun–than she expected.

[i]Page 21, 2014 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures, cited by Eriksen in her May 1, 2014 post, “The Coming Dementia Epidemic” for the Center for the Future of Museums blog.

This is a really interesting project! As my grandparents get older, I’ve been thinking a lot about their lives and stories (particularly how they can be a link to older generations that I was never able to meet). I wonder how this concept might work in the context of family history and if I could find historic photos that might resonate with my family.

Matt, I think the personalization aspect of this work has some incredible potential. Many of the pictures in the database in Oslo, for example, are geo-tagged with address information, meaning it might be possible to find photos of participants’ former homes and neighborhoods. I haven’t explored this with the folks I volunteer with simply because it’s a time-intensive process to collect the relevant information from participants.

If you’re looking for pictures that would resonate with your family members, you might start with Flickr Commons or the Library of Congress and see if you can find images of the places they grew up or lived earlier in their lives.

Emily,

I was so excited to read your post, I’ve been thinking for a while now how perfectly poised public historians are to engage with and be relevant to this demographic, but was struggling with how to translate that to my small short staffed county museum. Volunteering may be a way to test the waters, I also listened to a relatively recent NPR story on a similar project that is going on in some VA hospitals in the United States. I would love to stay informed as to how your project develops, keep up the great work!