We were "doing" place (before place was cool)

14 June 2013 – Robert Weyeneth

The Slater Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island was the first property listed on the National Register of Historic Places. (Photo by Juli)

The first Keeper of the National Register of Historic Places turned 90 this month. He is well-known professionally and personally among those who worked on behalf of historic preservation in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s. William J. Murtagh is equally well-known to today’s generation of preservation teachers and students. He is the author of Keeping Time, the wonderfully readable overview of “the history and theory of preservation in America.” The book was first published in 1988 and is now in its third edition because of its enormous popularity in college courses on historic preservation, architectural history, and public history.

There is another significant birthday approaching: the 50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act. Enacted in 1966, NHPA will reach the five-decade mark in 2016, just three years from now. The act established the National Register of Historic Places, a funding mechanism to promote preservation, a process for reviewing the effects of federal actions on historic resources, and eventually a system of state historic preservation offices, among other provisions. It is widely considered one of the most important achievements of the founding generation of the modern preservation movement. Some see NHPA more generally as a watershed moment in American thinking about the role of place in history and space in memory.

Joe Frazier’s gym in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania is among the newest National Register listings (Photo: National Register of Historic Places)

Usually these sorts of anniversaries catch me unawares. Too often they are also occasions for easy celebration and unexamined commemoration. But I am ahead of the game on this one, and I would like to use this perch to call on all of us who are involved in the enterprise of historic preservation (others welcome, too, of course) to inaugurate a set of conversations over the next three years to assess the history, impact, and legacy of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966.

Here in the digital age the terrain is wide-open, as never before, for these conversations. Through posts here on History@Work to the pages of The Public Historian, I can see multiple expeditions of discovery making their ways across the landscape, sometimes intersecting, sometimes skirmishing, sometimes re-supplying each other. I anticipate there will be points of convergence as we approach 2016, as well as diverse and distinct destinations. Let’s go for it.

Here are some quick thoughts:

- A 50th anniversary is an important occasion to mark. It is also a time for critical reflection.

- What stories from the trenches do educators have? Many of us who teach historic preservation use a nomination to the National Register of Historic Places as a term project assignment. At the University of South Carolina, my students have used the National Register very successfully to promote African-American heritage preservation. However, I’ll never forget a comment while working on a complicated project years ago: a sympathetic supporter announced that she thought the National Register was “racist.” She argued that because the criteria privilege the extant, African-American places are often dismissed as vernacular and vanished. Others who teach or write about historic preservation will have intriguing “war stories” of their own that can jump-start collective discussion.

- What stories from the trenches do practitioners have? How does NHPA look from the standpoint of historical consultants? Many of us who practice historic preservation have used the public process established by the National Register as a way to encourage acknowledgment, remembrance, and preservation of difficult and controversial pasts. Once upon a time, in an article in The Public Historian, I wrote about my own experience trying to do this in Centralia, Washington, which led to some conclusions about the challenges of undertaking public history projects in communities with historical secrets. Others will have fresher, more revealing stories about the utility and frustrations of doing historic preservation in public.

- What stories do our colleagues have from the perspective of state and tribal government? We should catalyze a nation-wide conversation on the legacy of the 1966 act by reaching out to state, territorial, and tribal historic preservation offices, as well as to the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers (NCSHPO).

- How does it look from inside the federal government? The National Park Service is the lead federal agency for technical information about historic preservation in the United States, and the National Register is housed within the NPS. The National Park Service will be marking its own birthday – the big 100 – in 2016.

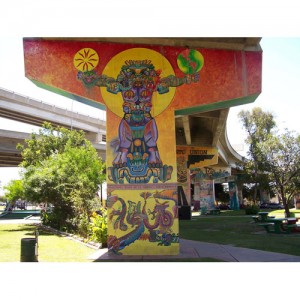

The murals in National-Register-listed Chicano Park, San Diego, California reflect the history of Chicano community organizing in the city. (Photo: National Register of Historic Places)

- How does it look from the perspective of engaged citizens? To put on my National Council on Public History hat for a moment, let’s reach out to the world of historic preservation and make it more aware of the world of public history. Let’s reach out to kindred organizations whose membership doesn’t always overlap with ours, even though it could. I’m thinking here of the National Trust for Historic Preservation but also of the many non-profit statewide and local preservation organizations. I urge NCPH members to get on the programs of national and regional preservation meetings, to get the word out about public historians and the interesting work we do; plus, NCPH could sponsor these sessions. I remember a National Trust meeting in San Francisco where a Bay Area resident stood up and announced that she had always thought of herself as a “community activist,” but as a result of the conference she realized she was also an “historic preservationist.” I’d like to see community activists and preservationists also think of themselves as “public historians.”

- Let’s get sessions, workshops, and field trips on the programs for the upcoming NCPH meetings in Monterey in 2014, Nashville in 2015, and Baltimore in 2016 that engage all these issues and the history, impact, and legacy of the 1966 act.

- From the immediacy of Twitter (follow @ncph) to the gravitas of The Public Historian, NCPH offers multiple platforms to catalyze and sustain conversation. This is a superb opportunity to begin symbiotic discussions through History@Work, looking toward a distillation of salient issues in a set of articles or roundtable in a special issue of The Public Historian that could be published in the 50th anniversary year of 2016.

Our friends and colleagues in the academy have been making “the spatial turn” in their scholarship for a while now. This is a welcome trend. But preservationists and public historians have been “doing” place for years, back when place wasn’t so cool. Let’s take stock on how far we’ve come by putting the last 50 years into critical perspective. And let’s ask a final less-obvious question: could today’s enthusiasm for the possibilities of place-based humanities be connected in any way to the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966?

~ Robert Weyeneth is the President of the National Council on Public History’s Board of Directors and Professor of History/Director of the Public History Program at the University of South Carolina. He can be reached at [email protected]. This article is also published in the June 2013 NCPH newsletter.

1 comment