Incorporating “Growth Mindset” into public history teaching

23 October 2019 – Paul Ringel

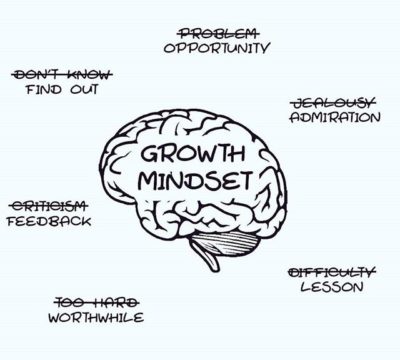

Growth Mindset v Fixed Mindset. Image credit: Paula Piccard

Last summer, when offered a rare opportunity to receive funding for course development, I applied for a university grant to test the value of incorporating growth mindset theories into my public history course. At first glance, these two pedagogies did not seem particularly compatible, but I was curious to see if I could combine them to a positive effect.

Growth mindset is a concept pioneered by psychologist Carol Dweck that suggests the ability to learn can be cultivated. Dweck places this concept in opposition to a fixed mindset, which perceives an individual’s intellectual capacities as unchangeable. Growth mindset has become a wildly popular idea in contemporary American education, ubiquitous from the walls of elementary school classrooms to the core of undergraduate curricula. In a 2016 Education Week Research Center survey, 98 percent of K-12 teachers agreed that schools should use growth mindset approaches. Yet scholars have widely argued that studies have failed to validate the theory’s effectiveness, and even supporters find it difficult to implement; only 50 percent of those survey respondents believed they knew how to change a student’s mindset.

In contrast to this abstract and process-focused idea, public history is a pragmatic, results-based instrument for taking history outside the classroom to illuminate its tangible impact on communities. In my proposal, I theorized that the hands-on work of public history might help to validate the hard-to-prove theories of growth mindset, and that association with the popularity of growth mindset might draw more attention to the important work of public history.

My first goal was to use public history to help students understand what growth mindset theories are meant to teach them. Dweck argues that “nobody has a growth mindset in everything all the time . . . something really challenging and outside your comfort zone can trigger” a fixed approach. Since public history puts students who are used to more traditional classroom settings in exactly those types of challenging and uncomfortable scenarios, I hoped that explicitly deploying growth mindset strategies in the classroom could help them cope with those stressful moments.

My primary strategy for working with students who already had some level of comfort with the concept was to keep the idea of a growth mindset explicitly at the forefront of our work. At the beginning of the semester, we had a discussion about what the term actually meant and how it might help with our project. In each week’s reflection essay, I included a question about how adopting a growth mindset might facilitate more effective—and less anguished—completion of assigned tasks.

The unique combination of students in this class made implementing my plan unexpectedly difficult. This spring was my fourth time teaching “The History Detectives,” an undergraduate course built around completing a group project based on local history. On each previous occasion, students displayed anxiety about community-centered tasks such as calling strangers, conducting interviews, and public speaking.

I based my theory that growth mindset strategies could help students manage their anxieties on this trend, but this time the students displayed very little of the discomfort that had hampered their predecessors. The group included two political activists, two international students, and two members of our university’s Bonner Scholars program, who already had extensive experience with community engagement. Their unusual chemistry and collective leadership smoothed the process of building relationships with our community partners: the Congregational United Church of Christ, a historically African American church in High Point.

This development was great for the group project, but not for my efforts to study the benefits of integrating growth mindset practices into public history. Amidst this dilemma, as I scrambled to adapt my plans mid-semester, I modeled growth mindset for my students. We talked about my anxiety, and the advantages of approaching this snag not as a roadblock, but as an opportunity to seek another area of student performance to evaluate in my study.

Within a few weeks, this opportunity emerged. Despite their comfort with our community partners, students were not working at a pace that would allow us to finish the project on time. The primary obstacle was a common one: struggles with time and stress management. Several students were coping with personal and professional challenges, and collectively those external factors were preventing our work from getting done.

In a larger, non-public history class, I would have talked to the struggling students to ensure they understood their standing in the class, and then placed the burden of seeking help on them. In this class, failure was not an option because the community was counting on our work. Instead of waiting for students to take responsibility, I developed a strategy they could use to address the problem.

Each week they met with me to make work plans, listing tasks they had to complete as well as work they might start early in order to avoid racing to hand in subpar work at the deadlines. Then I required them to estimate the time required for each task and add 25 percent more, since students habitually underestimate how much time assignments will take. The goal was to instill what I perceive as the foundation of growth mindset: approaching challenges as opportunities to improving learning practices rather than as barriers to accomplishment.

Undergraduate “History Detectives” pose with community partners during the debut of their exhibit. Image credit: Paul Ringel.

The work plans were not a miracle cure. Some students found them useful; others hated them. Most improved their productivity after I implemented this assignment, though it was also the midpoint of the semester, a time when responsible participants in my History Detectives class realize they have to improve their productivity or risk a very public failure. The work got done, and for the most part done well, without the late-night cram sessions that previous classes have required to finish their projects.

As with the work plans, growth mindset ideology did not revolutionize my public history course. It did, however, remind me of the value of spending more class time on process, particularly when the focus is on developing skills like resilience, adaptability, and persistence that are vital for undergraduates doing public history and most other kinds of work.

The “High Point Enterprise” featured the collaboration between High Point University students and community partners. May 14, 2019. Image credit: Paul Ringel.

This shift created a more empathetic learning environment without sacrificing work quality. Students responded well to the change; evaluations for this course, which already were perennially positive, jumped to their highest level yet. Meanwhile, the exhibit received rave reviews from community members and local press.

Based on this experience, growth mindset has become a useful tool in my public history toolbox. This experiment also garnered goodwill from the university administration, and if growth mindset can raise public history’s profile (and perhaps our budgets) in an era when humanities are marginalized on most campuses, so much the better.

~Paul Ringel is an associate professor of history at High Point University in High Point, NC.