Welcome to America: Embracing public history as public education

04 April 2016 – Donna Neary

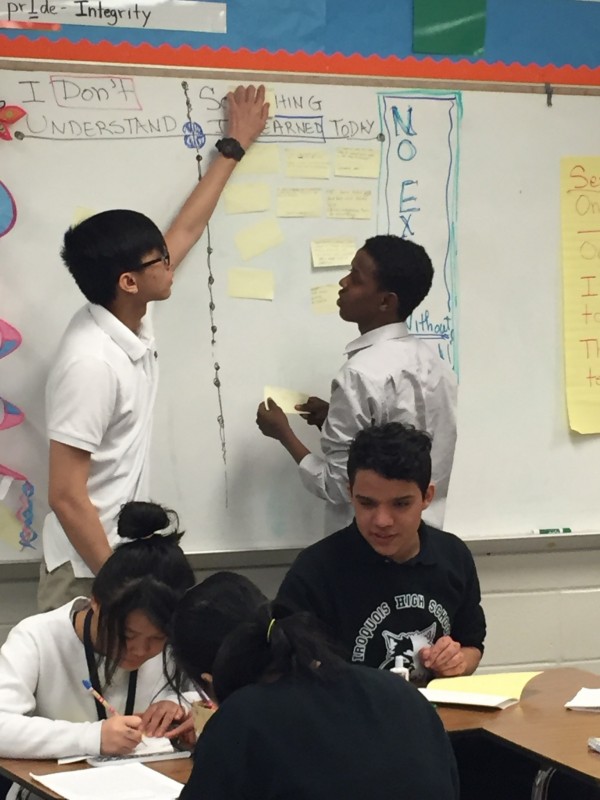

International Academy students work in Donna Neary’s classroom at Iroquois High School in Louisville, Kentucky. Photo credit: Donna Neary

My transition from public history to teaching was unplanned. After twenty-five years of working for local, state and federal governments, museums, non-profits, and as a consultant, I was unemployed, cut loose, and drifting out of sight of the public history mother ship. The funding for my state government position had been cut, and the real estate market was not favorable for consulting on tax credit applications or National Register of Historic Places nominations.

Although I’m still working on traditional public history projects during my evenings and weekends, my full-time gig now is as an English as Second Language (ESL) History teacher at Iroquois High School in Louisville, Kentucky. I work with students who are striving to graduate from high school and create solid futures for themselves, and their families. Most of my students are brand new to the United States. Some are enrolled in my class only days after arriving in this country; many are refugees from political oppression, and war-torn lands.

These students have multicultural sensibilities and are aware of the buttons to push or to avoid with classmates. Students translate for one another and show compassion and concern for others well beyond their years. These students are learning new social skills and they understand they must create relationships to get along in a new environment. My days are now filled with requests for assistance, and “Miss!” “Teacher!” and “Madame!” are shot rapid-fire through the classroom by students anxious to learn. Currently, students who speak 39 distinct languages populate the International Academy at the high school.

I am grateful to know these students and benefit beyond words by spending my days with smart, funny, and caring teenagers. And I have begun to regard teaching World History and Humanities to my students as a more direct form of public history, too.

My work in the classroom, like my work as a public historian, strives for social justice and equity for my students and sensitivity and transparency in the presentation of diverse cultural heritage. When I teach World History and Humanities to recent immigrants and refugees from around the world, my presentation forces me to examine society’s biases and to present lessons that are inclusive and balanced. For example, teaching imperialism to recently arrived students from the Belgian Congo or the Ivory Coast requires my lessons to give voice to the native populations affected, and to be clear about the motives of the conquerors –the industrial nations seeking new resources and new markets for goods.

Teaching my students about American culture and history constantly forces me to shift my thinking and presentations and to stay agile and responsive to what is happening in real-time in my classroom. For instance, during February we were learning about African American history. My students who have recently emigrated from the continent of Africa were confused by the term. During the lesson one student said, “I am not African American, I am not an American citizen, but I am black.” So that lesson was set aside and I taught about slavery and the brutal capture and transport of Africans to the Americas for labor. We discussed that those Africans are the ancestors of most people of color in the United States today. And students agreed on the term “Africans in America” to describe their own status.

Every new wave of refugees to our community brings questions. “Will we have enough desks and textbooks to serve these children?” we ponder. But we know that whether we are ready or not, they are coming. One of our cadre, a man who two decades earlier had immigrated to the US, said simply, “Let them come.”

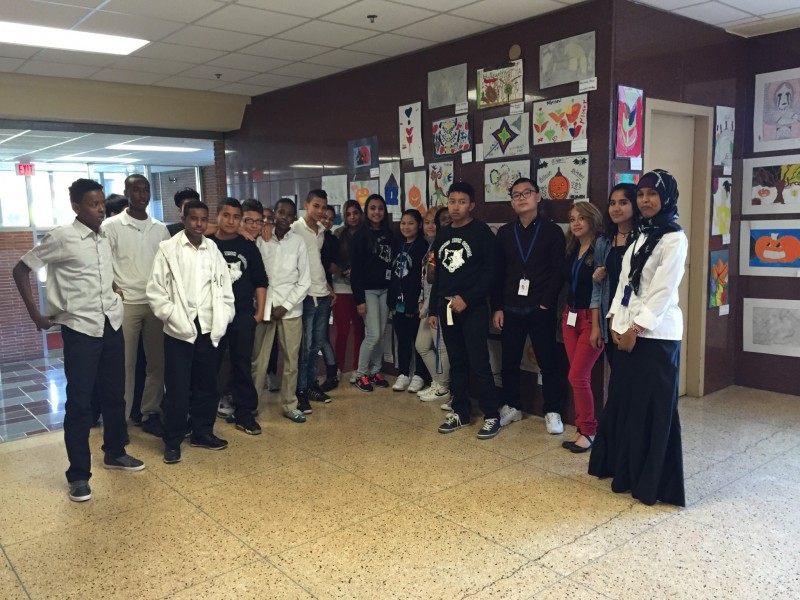

International Academy students pose in front of the Fall Art Show display at Iroquois High School. The show was the first time that these students displayed their work alongside American students. Photo credit: Donna Neary

We all smiled in recognition, knowing that they will come, and we will do our best to figure out the classroom logistics. And as I enter my classroom each morning, turn on the Smartboard, and change the date on our calendar, I smile again as I realize that I have not been set adrift. I choose to believe I am on a reconnaissance mission, seeking (and unexpectedly finding) new ways to bring public history, to the public.

~ Donna Neary is a teacher, a writer, and a public historian. A graduate of the Loyola University of Chicago Public History program, Neary was awarded a 2014 Artist Enrichment Grant from the Kentucky Foundation for Women (KFW) to assist her with travel costs to research a manuscript detailing the life of Leah Smith Lightner, an agent of change in post-World War II Germany.

Thanks, Donna for this thoughtful reflection of the high quality of work that you a always produce. So pleased for you and your students. What a blessing you are to them and to the community.

Veda,

You have been a model and a mentor for me as I grow in teaching. I miss the days of sharing a space! Donna

Mrs. Neary,

What a heart and passion you have for your students and for teaching! Thanks for being such a beacon to your students. I also appreciate you sharing this website with your colleagues at the University of Louisville.

Dr. Finch,

Thank you for the work you are doing at the University of Louisville to train teachers in cross-cultural competencies. My eyes were open, but the work I did in your course provided the resources and contexts for making those strategies work in my classroom. This should be a requirement for every public school teacher!

Great article, Donna, and glad you’re doing well and able to incorporate public history into your work. I was just talking to Ted K. about you at the recent NCPH meeting in Baltimore, which I had the chance to attend for a day.

Hi, Chris,

Thank you for your comments. I hope to get back to an NCPH conference again soon. I have met so many incredible people from around the globe, and many of my projects were enhanced from cocktail conversations and sessions. All the best! Donna