Reinterpreting Freeman Tilden’s Interpreting Our Heritage

19 September 2019 – Allison Horrocks

cultural heritage, public programming, interpretation, authority, National Park Service, shared authority, public history, working group, 2019 annual meeting, historiography

For the 2019 National Council on Public History Annual Meeting in Hartford, Connecticut, I had the pleasure of coordinating the Interpreting Our Heritage in the 21st Century working group with public historian Nick Sacco. Our goal was to take a fresh look at Freeman Tilden’s foundational text, Interpreting Our Heritage (1957), and to consider whether it required “repair work,” which was the annual meeting’s theme.

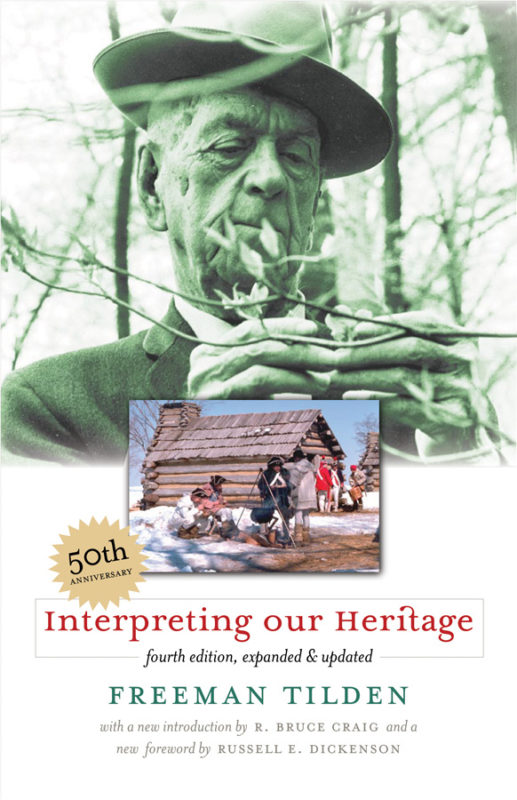

Anniversary cover of Freeman Tilden’s book Interpreting Our Heritage, fourth edition, expanded & updated. Image credit: UNC Press.

Many interpreters may readily remember Tilden’s fourth principle: “The chief aim of interpretation is not instruction, but provocation.” Beyond a few of his main ideas, however, others might rightly question what this text still has to teach us today. With this in mind, during our session we formed sub-groups around four topics: the usefulness of a historiography of interpretation, relationships between interpreters and historians, empathy and other concepts in interpretative practice, and the future of Tilden’s principles.

Working groups generally come together to solve a problem or to move a conversation forward. In this working group, I gathered that many of us were interested in parsing out whether a text as foundational as Tilden’s was still relevant to public historians today. Predictably, many of us started with how Tilden came to be as influential as he has been. Tilden earned his place of high regard back in the 1950s with the advent of Mission 66, which was an attempt both to overhaul existing practices and to codify professional interpretation within the National Park Service. His text has been printed and reprinted in various iterations ever since. Anecdotally, many participants shared that Tilden remained on training bookshelves and in public history syllabi. Yet others were keen to point out that Tilden was largely in the rearview mirror of their methodological practice, noting that his foothold only seemed strong at government-run heritage sites. Even as I heard suggestions of alterations or addendums, no one seemed ready to eliminate all of Tilden’s principles from their toolkit. Though uses and opinions vary, I suspect that Interpreting Our Heritage is not going out of print anytime soon.

In my own career, Tilden’s work was a basis for my introduction to interpretation. When the idea first came up to do this working group, I turned once again to my dog-eared copy. I can admit that I felt only somewhat assured of Tilden’s continued relevance.

Part of what was motivating me to be a part of this conversation about Tilden was the question of authority. I was interested in the privileged position that some people associate with this particular book and author, but even more so with the role of the interpreter as an authority. With at least some practitioners returning to this text again and again, I figured we ought to really consider what Tilden has to say about learning and developing as an interpreter.

To begin with, Interpreting Our Heritage does not serve as a how-to for building any one kind of public program. Instead, it provides a set of principles and an overarching view of the interactions between three groups: specialists who produce research, interpreters who deliver programs, and visitors who take part in the interpretive experience. To a large degree, Tilden encourages historic interpreters to use expertly sourced material to build a program that provokes and enlightens the visitor. While using the work of other specialists, Tilden’s interpreter is also encouraged to be somewhat aware of visitors’ knowledge. Notably, Tilden places far less emphasis on what a visitor or audience member may bring to a site.

In thinking about this triangulation, I considered the enduring fact that interpreters are charged with transforming a seemingly unmanageable amount of information into something suitable for the public. I was also struck by the fact that Tilden stops short of arguing that interpreters should claim a special kind of expertise for themselves, in the realm of interpretation or otherwise. Lest we dismiss Tilden too soon, I want to question whether we have fundamentally changed how we think about expertise since the ink first dried on Interpreting Our Heritage. For the most part, interpreters at historic sites still rely on outside expertise for authoritative analysis. They are also expected to be confident enough in the material to explain it to the public. Let us acknowledge that there is a tension here. Further compounding this dynamic is the fact that interpreters are now also called upon (to a much greater degree) to honor the knowledge that their audiences bring.

But there are still other changes worth considering. Interdisciplinary fields like museum education and environmental education, as well as practitioners of audience-centered engagement, have done much over the past decades to add to the interpreters’ toolkit. Compared to when Tilden is writing, there is so much more to know and so many new ways to share that knowledge. To take just one example: compare the range and depth of scholarship on women’s private lives in the 1950s and today. House museum interpreters can turn to a complex historiography on domesticity and gender; on a practical level, they also need to be able to speak to the uses of specific objects and individual biographies. Yet how, precisely, an interpreter ought to learn to balance interpretive skills and subject-area knowledge remains insufficiently addressed by public historians.

Within our working group the question of content knowledge and expertise came up in various ways, primarily in discussions of relationships between historians and interpreters. In the sixty-plus years since Tilden’s guidebook on interpretation was published, there have been not one but several revolutions in the way people teach, study, and interpret history. For all that has changed, there remains a critical divide between historian and interpreter; the former is often thought of as a creator of knowledge, the latter, a consumer and disseminator. As working group participant Anne Whisnant rightly pointed out in some of our discussions, all historical analysis is a process of interpretation. Both historians and interpreters work with primary documents, secondary sources, and other resources to reveal something about the past and the present. With this in mind, I wonder what could be gained by acknowledging that both historians and interpreters are involved in the work of interpreting the past. We do not need to flatten the differences in training and kinds of expertise that historians and interpreters possess. What we can do is question why interpreters are still not often seen as authorities in their own right. Interpreters are now often called upon to form symbiotic relationships with their audiences. As we question that dynamic, certainly other power relations and lines of authority are worth another look, too.

Tilden provided a blueprint for interpretive practices, but his conceptualization of the relationships between interpreters, experts, and audiences are far from the final word on interpretation. Indeed, his writing on training and visitors may not resonate at all with your vision of interpretive practice. It is for this reason that I am not prepared to issue a call to toss all extant copies of Tilden to the wind. If you have read about this working group with healthy skepticism, I hope that Tilden’s basic triangulation of knowledge–interpreters conferring the work of experts to relatively passive visitors–is foreign to your practice. But I am not convinced that this formulation has really gone away.

Many at the 2019 NCPH annual meeting acknowledged that interpreters today are doing complex social justice work through dialogue and other programming. This kind of work was also modeled at the plenary on gun violence, where various kinds of expertise were honored and integrated into the program. Generally, interpreters do this work with a far keener awareness of their audiences and, in many cases, with tools Tilden could not have dreamed of. This is a new kind of authority, and we ought to look closely at the basis for the knowledge (in terms of content and special tools) needed to do this well. Ultimately, we can and should honor this as a form of expertise. This means doing more than admonishing the “sage on the stage” model while also demanding an increasingly high level of sagacity of interpreters.

If we want to truly share authority, we have to continue to rework what that means in relation to our colleagues, our audiences, and others in the field. Had I been forced to draw one conclusion from our session, it would be this: Tilden’s writing is still useful to “think with,” even as it remains (like all historical documents) a product from another time. Interpreting Our Heritage will stay on my shelf, but it will not stand alone. Tilden will be joined by the works of historians, fellow interpreters/experts, and members of the community in which I work.

A note about this working group: if you have interpretation resources you would like to share, we welcome contributions to our website: Interpreting Our Heritage in the 21st Century.

~ Allison Horrocks is a Park Ranger at Lowell National Historical Park in Lowell, MA. She tweets as @allisonhorrocks.

And herein lies one of the biggest problems in our society today: “. . . acknowledged that interpreters today are doing complex social justice work through dialogue and other programming . . . modeled at the plenary on gun violence”

WRONG – it is not any interpreters job in a park, a museum, a school, or otherwise to make comments on social justice ESPECIALLY to our children. This is the PARENTS place . . . while I realize that many parents are not currently fulfilling this duty to the best extent possible, conversation around the FAMILY DINNER TABLE is where social justice issues should be hashed out – in a safe and loving envrionment. Certainly not be a HISTORIC interpreter with their own opinions and upbringing. Discuss the history and make it relatable, leave the current issues to the families.