Love Letters to Philadelphia: Gendering an urban brand (Part 2)

11 July 2012 – Mary Rizzo

“There was this young man from West Philadelphia,” our tour guide, Barbara, told the group of us assembled on hard plastic chairs. “He was a tagger, a graffiti artist, kept getting in trouble. He finally got sent to jail, and when he got out his girlfriend told him she didn’t want him around their baby anymore. But he was determined to win her back and since she worked at SEPTA [Philadelphia’s transit authority], he painted the murals that we’re going to see today along the train line to prove his love.”

“There was this young man from West Philadelphia,” our tour guide, Barbara, told the group of us assembled on hard plastic chairs. “He was a tagger, a graffiti artist, kept getting in trouble. He finally got sent to jail, and when he got out his girlfriend told him she didn’t want him around their baby anymore. But he was determined to win her back and since she worked at SEPTA [Philadelphia’s transit authority], he painted the murals that we’re going to see today along the train line to prove his love.”

We all knew that, strictly speaking, this wasn’t true. As described in my last post , Philadelphia’s Love Letter murals were created by Steve Powers as part of the renowned Murals Arts Program (MAP), not as some romantic gesture. But Barbara was following the first rule of being a good tour guide–don’t just tell facts, tell stories–and the baker’s dozen of us gathered for the Sunday tour were rapt. Mostly between 20 and 40 years old, the multiracial group was made up of couples except for me: a mother and daughter traveling from Australia, a student from D.C. up to visit his girlfriend, and three others, from Philadelphia, the suburbs, and farther afield. As quickly became clear, these binaries structured the group dynamic, as the tour was an excuse to be with each other, rather than meeting strangers.

As I noted previously, the Love Letter murals can be seen as part of a process that uses the concept of love to create a feminized city that is receptive to tourists, travelers, and, ultimately, economic development. Having examined the murals within this context, I was curious how individuals interacted with them. In particular, I was interested in how MAP interpreted these murals, Philadelphia’s most popular, on their twice-weekly tours. How would a guided tour shape people’s reactions to and understanding of the murals? How would this tour, which unlike MAP’s walking tours used the elevated train, connect with the neighborhood? If the murals’ implicit goal is to place West Philadelphia within a larger Philadelphia that is ready to be loved, was the tour an essential part of this process or did it offer a counterpoint?

Before getting on the train, we started with a Powerpoint presentation in MAP’s offices. As Barbara described MAP’s beginning as the Anti Graffiti Network, it became clear that its product is not the murals themselves, but a replicable process for public artmaking that can be exported to cities worldwide.[1] This process would be familiar to public historians—area residents collectively decide that they want a mural (though exactly what that means is unclear) and then work collaboratively with artists to develop the content. Painting is done by groups, including community members, but also students, at-risk youth, and others. While some artists charge reduced fees for their services, these murals aren’t cheap—the most expensive, underwritten by Lincoln Financial, cost more than a quarter of a million dollars.

With this background information, our group follows Barbara to the subway. Once the train goes above ground, she tells us, she’ll point out the murals and talk about what they mean. We’ll get off the train at just two points, once to look at a particularly good view of several murals and the other to get on the train coming back to Center City. In other words, unless someone leaves the tour, our collective feet will not touch the pavement, an extraordinary fact that suggests that the tour’s impact on the neighborhood (and vice versa) is minimal. There will be no purchases from local stores to spur the economy, for example, and there will be little interaction with the people who live there.

In this way, the Love Letters tour differs significantly from both the walking tours offered by MAP and the traditional guided tour that many public historians have both led and analyzed. Looking at the murals only from the train and two platforms abstracts the murals from the city, making it nearly impossible to read any kind of narrative in the tour itself. Instead, we travel through space, high above the street, with little or no sense of where we are in relation to any of the markers that define a city neighborhood. While the choice to stay on the train seems to be justified by the murals’ locations since many are blocked by other buildings at street level, this is a marginal rationale at best. Most of the members of my group engaged with the murals through photography, difficult on a train that stops for only a few seconds. And, of course, while Barbara would try to point out as many murals as possible, for those of us who weren’t lucky enough to sit near a window or be looking in the right place, many sped by before they could be fully comprehended. Even on the two platforms where we stopped, metal safety grating obscured the view and made photos hard to take. Clearly, a hybrid tour could have combined the train view with a few blocks’ walk to see certain murals for a more sustained duration. At street level, though, any group would also be confronted by cracked sidewalks, potholed streets, and the trash that blows in and around the gutters, swirling around pedestrians’ ankles like a pestering cat.

In this way, the Love Letters tour differs significantly from both the walking tours offered by MAP and the traditional guided tour that many public historians have both led and analyzed. Looking at the murals only from the train and two platforms abstracts the murals from the city, making it nearly impossible to read any kind of narrative in the tour itself. Instead, we travel through space, high above the street, with little or no sense of where we are in relation to any of the markers that define a city neighborhood. While the choice to stay on the train seems to be justified by the murals’ locations since many are blocked by other buildings at street level, this is a marginal rationale at best. Most of the members of my group engaged with the murals through photography, difficult on a train that stops for only a few seconds. And, of course, while Barbara would try to point out as many murals as possible, for those of us who weren’t lucky enough to sit near a window or be looking in the right place, many sped by before they could be fully comprehended. Even on the two platforms where we stopped, metal safety grating obscured the view and made photos hard to take. Clearly, a hybrid tour could have combined the train view with a few blocks’ walk to see certain murals for a more sustained duration. At street level, though, any group would also be confronted by cracked sidewalks, potholed streets, and the trash that blows in and around the gutters, swirling around pedestrians’ ankles like a pestering cat.

Nonetheless, the murals compelled the group’s attention completely. As one young African-American man from D.C. told me, “They’re really unique to Philadelphia. It’s just beautiful,” suggesting that the murals are added value to Philadelphia’s tourism potential. As Barbara struggles to point out murals before the train moves on, she notes that many make reference to the buildings that they are on as well as the theme of romantic love. “Safe for valuables” is painted on the side of a bank, for example, while “Picture you, picture me, picture us,” is on a former camera store.

The fact that we are not on the street, though, means that we cannot see the disconnect between the bright murals and the empty storefronts. Barbara notes that the artist who created the murals is a sign painter, which shows in their eclectic aesthetic. The style references a history of urban signage that is mostly absent from the suburbs or more upscale urban areas, where national chains or modern graphic design predominate. However, in West Philadelphia, the murals share space with real signs that look much like them, commenting slyly on the lack of economic activity in the neighborhood.

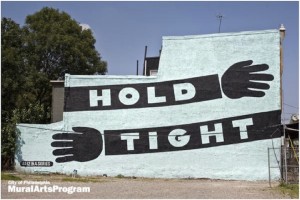

“Hold Tight” by Stephen Powers. (Photo by Adam Wallacavage, used with permission of the Mural Arts Program)

The Chances Lounge, a bar located two blocks west of the Hold Tight mural, has a sign that seems to have inspired the mural, with their nearly identical parallel outstretched arms, showing how the signage already in existence in the neighborhood was mirrored by the Love Letter project.

What’s most striking about the murals is how their vernacular quality differs from the more painterly style of the city’s other murals, suggestive of the shared authority that created them. For example, one mural is of a heavily tattooed arm, which Barbara tells us is supposed to belong to former Philadelphia 76ers basketball player Allan Iverson. While this references his former team’s home city, the image has its own resonance, as the disembodied limb hovers above the roofs of other buildings with its aggressively masculine imagery, a strange inclusion in the otherwise coyly witty images.

What also haunts and confronts MAP’s project are the unofficial murals painted by neighborhood organizations and residents. One that whizzes past displays Islamic messages, showing how the mural style can be utilized for purposes outside of MAP’s catchment. Barbara points out one large mural that reads “Drugs create thugs, Guns kill sons, Love makes love: The choice is yours,” and quickly explains that even though it is painted clearly to look like a Love Letter mural, even down to its font and composition, it is not. (However, MAP maintains all the murals in the neighborhood, official or otherwise.) Rather than a vaguely romantic sentiment, this mural speaks specifically to the social problems that plague this neighborhood and uses love to describe an active process by which individuals shift their actions towards each other and their place of residence. What kind of love brought people together to make this artistic statement, I wonder? But the train moves on before I can ask.

~ Mary Rizzo

(The third and final part of this series will be posted next week. Part I is posted here. Photos are by the author unless otherwise noted.)

[1] George Ritzer, in The McDonaldization of Society, argues that the fast food giant’s real product is a rationalized process of labor. Similarly, MAP may produce murals, but what makes it unique is the step-by-step method that it has created to do so successfully, which can be adopted nearly anywhere.

1 comment